Happy Sunday, readers!

Welcome to DisFact, a weekly newsletter about Indian politics, policy and the economy. I am Samarth Bansal. If you find this newsletter useful, please forward it to a friend. If you’ve been forwarded the newsletter, here is the signup link. Here is the list of all previous issues.

The 2019 Indian general election is likely to be the world's costliest. The Delhi-based Center for Media Studies estimates that it will cost around Rs 50,000 crores. Money matters in elections—a lot.

Yet, India’s campaign finance laws are ridiculously opaque: there is zero transparency in political contributions (who gave how much to whom, we barely know); audited party expenditure accounts are a joke (parties don’t report actual spending); and the Election Commission of India doesn’t have enough enforcement powers (say, for instance, to cancel candidature for misreporting personal wealth).

And there are no signs of improvement: the “electoral reforms” introduced in 2017 have made political funding even more opaque.

In today’s issue: a deep-dive into the role money plays in Indian elections

The rise of self-financing candidates

Why are Indian elections so expensive

How the so-called electoral reforms have made things worse

The rise of self-financing candidates

There is a massive wealth premium in winning elections. Richer candidates are more likely to win.

Of the 21,000 candidates who contested the last three general elections, the wealthiest 20% of candidates were more than twenty times more likely to win election that the poorest 20%. (Read more)

In fact, the number of crorepati Lok Sabha MPs (whose self-disclosed assets totalled at least one crore) increased from 30% in 2004 to 82% in 2014, implying the growing role of private source of campaign funding in India.

Why are Indian parties increasingly dependent upon such wealthy candidates?

There is little incentive for third-party actors — eg businessmen — to finance an individual’s campaign instead of giving directly to the party. The root cause, Neelanjan Sircar of Ashoka University argues, is the weak representative role of India’s elected politicians.

Simply put: A party’s policy decisions are made by a small coterie of party elites. The same elites also decide who gets the party’s ticket to fight elections—a signal of low “intra-party democracy”. Even if a candidate wins the seat, “anti-defection laws effectively prevent elected representatives from having much of a role in policymaking”—meaning elected politicians can rarely, if at all, vote against the party line.

That’s why it’s optimal for big donors to fund the political party rather than an individual politician. With little opportunity to raise outside funds, candidates must largely finance their election campaigns—leading to the rise of wealthy candidates. (Read more)

Why it matters: The increasing role of private funding leads to self-selection in candidates who run for office (only a small subset of the population — rich folks — can realistically win), meaning elected politicians may become worse at representing their constituents. Plus, candidates may view an election contest as an investment, leading to greater levels of corruption as elected legislators try to recover the electoral costs.

Why are Indian elections so expensive

There is no credible data on real expenses to figure out how much and where do politicians spend during the campaign. It’s an open secret that the reported spending is orders of magnitude smaller than actual spending.

Where do they spend: Logistics (material for rallies and processions, vehicles, speakers, chairs, tables, posters); paid political participation (hired crowds); paying wages of political workers, food expense during the campaign; “vote-buying” (handing out of cash to voters, distribution of alcohol, hosting large public meals).

How common is “vote-buying” or “gift-giving”? Giving gifts to voters is technically illegal, but it is still very common.

Jennifer Bussell, a professor of political science at UC Berkley, surveyed over 2,500 incumbent politicians in Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh between 2011 and 2014 and found that “more than half of respondents across all levels of office—and nearly all at the state and national level—report that candidates are pressured to distribute gifts on the campaign trail.” (Read more)

Gift-giving is so prominent, Bussell found, that politicians estimate at least a quarter of voters receive a gift. Simon Chauchard, a professor at Columbia University, found in a survey that politicians in Mumbai spent anywhere between 19% and 64% of their budgets on gifts to voters.

Does it actually help? Opinion is divided. Pradeep Chhibber and Rahul Verma of UC Berkeley argue that the influence of cash and goodies distributed during elections on vote choice is marginal. Secret ballot ensures there is no direct method of purchasing support or votes: a citizen can take gifts from one political party — or from every party — and still vote independently.

Read more: “Money can’t always buy votes”; “Death of patronage?”

Why is campaign cost increasing?

While gifts and bribes are prominent, that’s not the sole cause of rising campaign costs. Here are two other reasons:

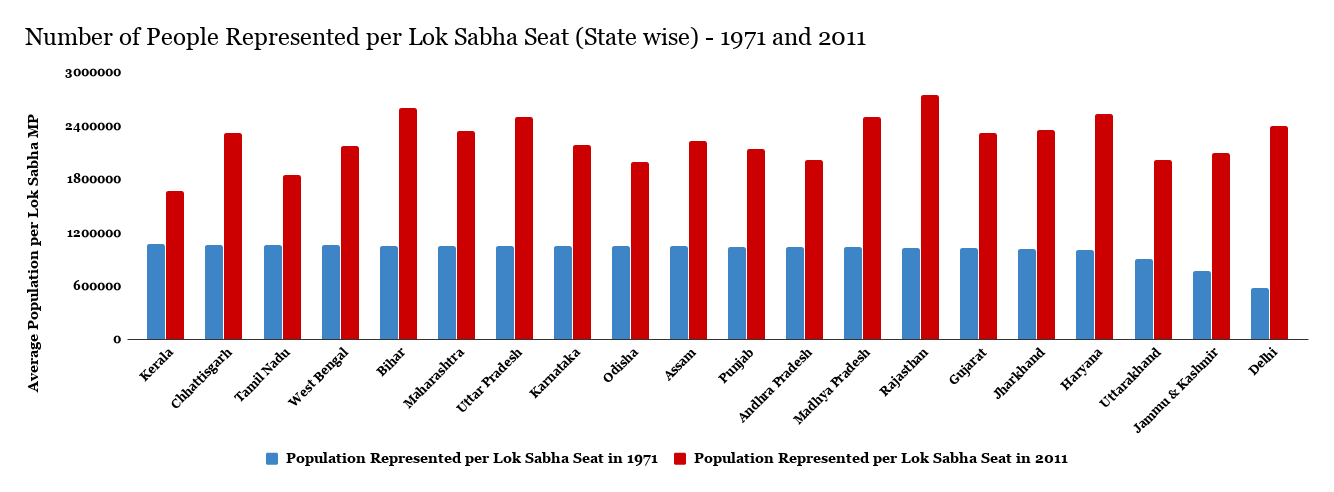

1. Increase in constituency size: Indian constituencies still represent populations based on the 1971 census. In 1971, each Lok Sabha MP represented around 7.24 lakh people in 1971; now, the figure stands at 17.11 lakh people, as per 2011 census. From the IDFC institute:

Larger populations, obviously, require candidates to spend more.

2. Rise in political competition: “A steady rise in political competition and in the number of candidates has sparked an arms race in campaign spending. More candidates automatically mean more uncertain elections, and hence costlier contests for candidates who are forced to match the expenses of their competitors.” (Read more)

What this means: According to Simon Chauchard, “costlier elections may not result from lower levels of morality in the political class or from a surge in bribe giving. They instead likely flow from rising levels of political competition, which may be doing harm as well as good.”

How the so-called “electoral reforms” have made things worse

(Chart from Bloomberg Graphics)

India witnessed major changes in campaign finance regulation in 2017.

Limit for cash donations to political parties: reduced from Rs. 20,000 to Rs. 2,000.

That won’t help as much: “Parties now will resort to multiple receipts of Rs 1,999 each like they did to evade the old limit of Rs 20,000 cash donations, issuing multiple receipts of Rs 19,999,” Jagdeep Chhokar of the Association for Democratic Reforms told Scroll.)

The cap on corporate donations removed: Earlier, the maximum a company could donate was limited 7.5 percent of a company’s average net profits over three years and had to declare the recipient. Now, there is no limit on donation, and there is no requirement to declare how much they donated and to which party.

Shell companies: the change also permits new companies to donate to parties, opening the door for shell companies — bogus and inactive entities that exist only as a postal address — to be set up just to route money for this purpose.

Parties can now get foreign funding: “Previously, all subsidiaries of international entities were treated as overseas donors and not allowed to make political contributions. Now, if a foreign firm has a stake of less than 50 percent in a company operating in India, that unit can fund Indian elections.”

Electoral bonds: The Finance Bill 2017 enables the creation of a new financial instrument called an ‘electoral bond’ which can be “anonymously bought and deposited in the account of the beneficiary political party.”

Anyone can buy an electoral bond at the government-owned State Bank of India in denominations ranging from 1,000 rupees to 10 million rupees ($14 to $140,000). Afterwards, they are delivered to a political party, which can exchange them for cash. They don’t carry the name of the donor and are exempt from tax. (Read more)

What the government says: electoral bonds will increase transparency as the money will go through the banking system and political parties have to declare how much they have received. Anonymity is essential, they argue, to protect donors “against India’s ‘vindictive’ political culture in which parties could penalise donors for funding rival political forces.” (Read Finance Minister Arun Jaitley’s Facebook blog for more details)

That’s just another spin from Mr Jaitley. Take all the changes together, and there is absolutely no way that the new rules make the system more transparent—far from it. In fact, it’s even more opaque. Milan Vaishnav, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wrote: “the floodgates are now open for limitless, anonymous political giving.”

So now, it’s more difficult to know who is funding whom, and the favours corporations receive in return when government policy is formulated or resources are allocated.

Electoral trusts: Electoral bonds fall in line with other “reforms” introduced in the past to protect anonymity of donors. Back in 2013, while companies were still required to report political contributions, the then Congress-led Central Government created another layer of opacity in the process by recognising Electoral Trusts: “secretive entities that collect donations on behalf of India’s biggest corporates” and disburse the money to multiple political parties—so again, you can’t trace back which company gave money to which party. (This Hindustan Times graphic explains everything about electoral trusts.)

Who is receiving the most money from electoral bonds: BJP. 95% of the electoral bonds purchased in 2017-18, a little over Rs 210 crore, went to India’s ruling party. According to Factly, this accounts for around 20% of the total funds raised by the BJP during the year.

Who is buying the electoral bonds: In terms of value, bonds of Rs 1 crore and Rs 10 lakh denomination accounted for close to 99.9% of the total value of bonds purchased till October 2018, Factly reported. It is highly likely that these bonds are purchased by corporates rather than common citizens.

What was demonetisation’s impact? In an interview with the Indian Express, OP Rawat, the former Chief Election Commissioner (he retired in December), was asked if the note ban “had any effect on black money” and its role in elections. No impact, he said.

Absolutely nothing. After demonetisation, we seized a record amount of money during elections. Even in elections to these five states, seizures have been close to Rs 200 crore. It shows that money during elections is coming from sources which are very influential and are not affected by such measures.

More

1. What to do? In the Hindustan Times, Devesh Kapur, E Sridharan and Milan Vaishnav, the editors of the book ‘Costs of Democracy: Political Finance in India’, laid out an alternative approach to reform political finance. It’s worth a read. (Read here)

2. How a legal loophole allows BJP MP Rajeev Chandrasekhar to hide his full wealth from election panel: A Scroll investigation published this week shows how Chandrasekhar—the major investor in Arnab Goswami’s Republic TV—did not reveal the largest company he controls in the election affidavit, and a regulatory loophole that makes it okay.

Say hello!

Comments? Feedback? Suggestions? Write to me at samarthbansal42@gmail.com or hit reply to this email. And if you find this helpful, please spread the word. Thank you!