Happy Sunday, readers!

Welcome to DisFact, a weekly newsletter about Indian politics, policy and the economy. I am Samarth Bansal. If you enjoy this newsletter, please forward it to a friend. If you’ve been forwarded the newsletter, here is the signup link. Here is the list of all previous issues.

One of the core beliefs that makes democracy a good political system is that elections serve as an effective check on power and allows citizens to hold the government accountable. If political leaders don’t deliver, voters will choose the alternative in the next cycle.

That raises the question: How do voters evaluate a government’s performance?

To be sure, there is no single metric to analyse performance. As T N Ninan, Chairman of the Business Standard, wrote in this excellent essay published in the January issue of the Seminar magazine:

There are different ways to measure a government’s performance: against one’s expectations, against the promises made, and against its predecessor’s record. There are also multiple frameworks within which to judge: political, economic, social, institutional, and national security/international relations. (Seminar)

Ninan’s essay is a must-read if you are looking for a balanced and nuanced take on the performance of the Modi government.

In today’s newsletter, I specifically look at perception of economic policy. Does a government’s economic performance matter when people go out to vote? How do people think about the state of the economy? Do facts even matter?

Our views on the state of the economy

Jobs crisis. Rural distress. Farm loan waivers. Income guarantee schemes. Growth figures. At least until two weeks ago, these issues were on the top of our politicians’ agenda. It appeared that the economy would dominate the 2019 campaign as it did in 2014. After the tragic Pulwama attack, I am not so sure if it will.

Regardless, the questions are still significant.

1. How do people decide how the economy is doing?

In an interview with The Interpreter columnists of the New York Times, Ryan D. Enos, a Harvard political psychologist, said that social scientists have no idea about “how people learn about their economic environment” and “how they decide whether the economy is good or bad.”

Crucially, Enos said, it’s possible that some of the things that could influence people’s economic perceptions might not seem very “economic” at all. Stores in town closing down might give people a sense of economic decline even if their own incomes remain high, for instance. So could their children taking years to begin their careers, or having to move far away from home to do so.

More:

Enos offered a useful reminder that we might not actually know what “economic issues” are. It’s possible to be wealthy and economically anxious, and to be poor but economically optimistic.

2. Feelings drive perception about the economy

In her recent How India Votes column, journalist Rukmini S argued in Scroll :

…the possibility is high that perception is what matters more than actual economic data. Voters appear to conflate their feelings about an administration or its leader with actual economic growth.

The inflation conundrum: Rukmini cited one example to back the claim. Inflation has gone down under the Modi government but most people think it has gone up.

Asked on the eve of every budget of his term so far whether Modi has been successful in reducing inflation, respondents to a nationally representative survey conducted by CVoter agreed in the government’s early years, but then swung towards saying prices were shooting up.

This, despite the fact that as the journalist Roshan Kishore points out in the Hindustan Times, inflation has steadily fallen since Modi took office, largely on account of low crude oil prices.

One possibility is that with sectors of the economy where most people work, like agriculture and construction, not growing fast or delivering better incomes, people are feeling the squeeze even if prices are not rising.

3. Evidence from the US

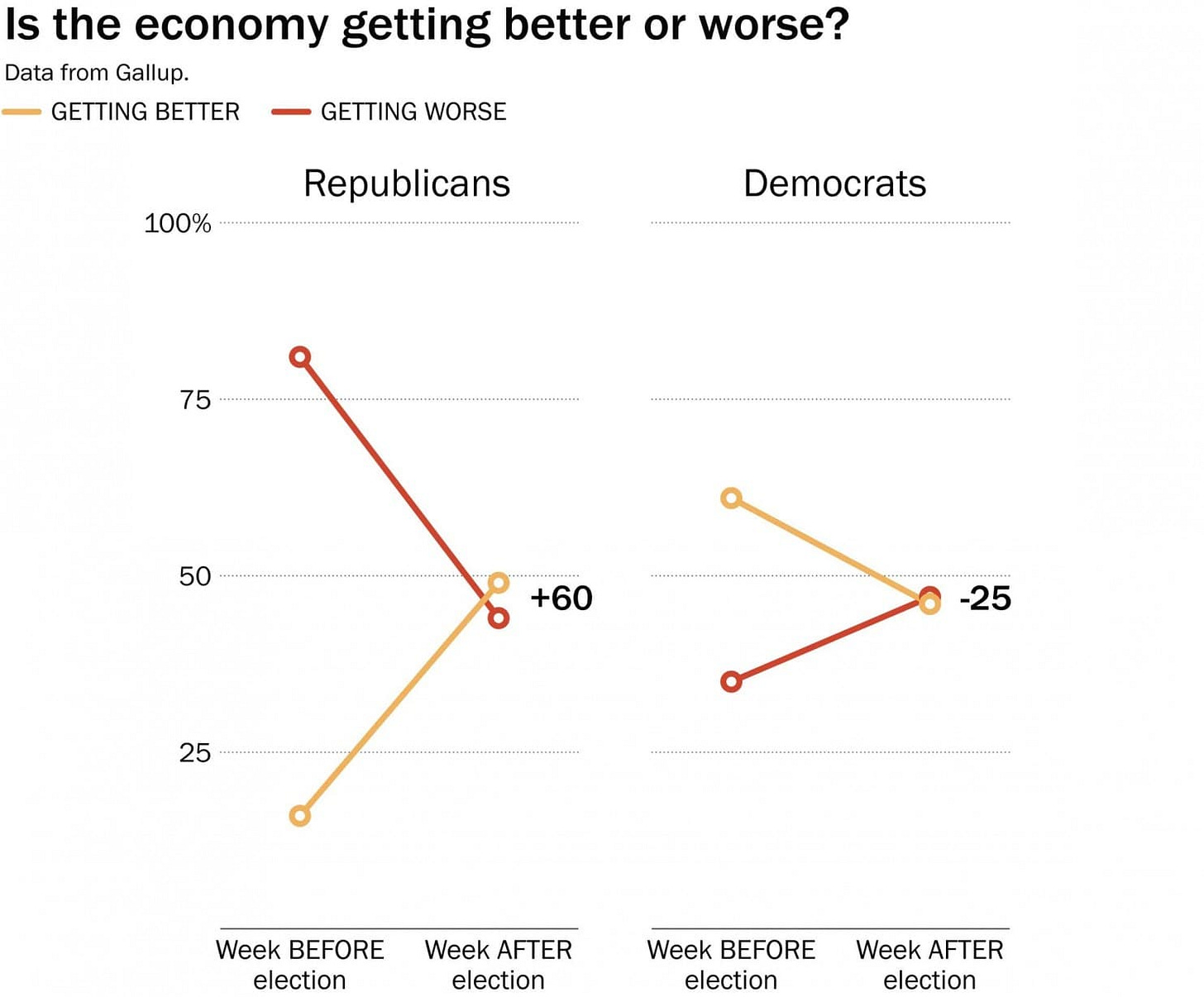

Gallup, a polling agency, regularly tracks economic confidence numbers in the US. It polled members of the two major American parties — Republicans and Democrats — before and after the 2016 US Presidential Election that led Donald Trump to the White House.

Results: See the chart below. It is one of the most striking things I came across after the US election.

Explain: Gallup’s data revealed that after Trump, a Republican, won the election, Republicans and Republican-leaning independents had a much more optimistic view of the U.S. economy's outlook than they did before the election.

A week before the election, just 16% of Republicans said the economy was getting better. In the week after the election, 49% said it is getting better.

Same for Democrats: The percentage of Democrats who said the economy was getting better reduced from 61% a week before the election (when Barack Obama, a Democrat, was the President) to 46% a week after.

Only partisanship can explain this huge shift in perception. When the leader you like is in the power, the economy looks good, and vice versa.

What does this mean

Three things can be simultaneously true:

Voters are concerned about the economy and factor in issues like jobs and prices in their decisions.

Voters are more informed today than anytime before given the diversity of information sources.

The evaluation of “economic performance” is not always based on objective facts. It’s driven more by one’s feelings and political orientation.

Why it matters

“How can people judge whether a party is effective if there is no sense of objective truth?” economic journalist Neil Irwin wrote in the New York Times.

…people don’t simply look at how the economy is doing and whether the nation is at peace, and decide whether to vote for the incumbent party based on those realities. Instead they have political preferences that stay in place regardless of how the country is doing. That implies that political parties won’t be rewarded for delivering good performance, or punished for bad performance.

Related readings

1. The problem with facts (Financial Times):

This is a great piece by economist Tim Harford that I often go back to for a reality check. Do facts matter?

Facts, it seems, are toothless. Trying to refute a bold, memorable lie with a fiddly set of facts can often serve to reinforce the myth. Important truths are often stale and dull, and it is easy to manufacture new, more engaging claims. And giving people more facts can backfire, as those facts provoke a defensive reaction in someone who badly wants to stick to their existing world view.

…

The problem here is that while we like to think of ourselves as rational beings, our rationality didn’t just evolve to solve practical problems, such as building an elephant trap, but to navigate social situations. We need to keep others on our side. Practical reasoning is often less about figuring out what’s true, and more about staying in the right tribe.

2. The Real Story About Fake News Is Partisanship (New York Times)

3. Why People Continue to Believe Objectively False Things (New York Times)

This is your brain on terrorism

If you feel anxious in the current political climate, watch this video from Vox.

We watch news coverage of terrorism because we think it'll make us better informed about how to keep ourselves safe. But what if it does the opposite?

Say hello!

Comments? Feedback? Suggestions? Write to me at samarthbansal42@gmail.com or hit reply to this email. And if you find this helpful, please spread the word. Thank you!